⚠️ This content has been written a long time ago. As such, it might not reflect my current thoughts anymore. I keep this page online because it might still contain valid information.

Object Calisthenics

— Clermont-Fd Area, FranceJump to: TL;DR

2016-05-11 // This article has been translated into Portuguese by @paulorodriguexv, thank you!

Last month, I gave a talk about Object Calisthenics at Clermont’ech’s APIHour #2, a local developer group based in Clermont-Ferrand (France).

I discovered Object Calisthenics almost two years ago, but I wasn’t open-minded enough to give them a try. A year ago, Guilherme Blanco and I were drinking beers in Paris. He told me that Rafael Dohms and him ported the concept of Object Calisthenics to PHP. That was awesome, and I decided to learn, understand, and try these rules. I am now convinced that these rules are really helpful, and that trying to respect these rules help you write better Oriented Object code.

Cal • is • then • ics - /ˌkaləsˈTHeniks/

Object Calisthenics are programming exercises, formalized as a set of 9 rules invented by Jeff Bay in his book The ThoughtWorks Anthology. The word Object is related to Object Oriented Programming. The word Calisthenics is derived from greek, and means exercises under the context of gymnastics. By trying to follow these rules as much as possible, you will naturally change how you write code. It doesn’t mean you have to follow all these rules, all the time. Find your balance with these rules, use some of them only if you feel comfortable with them.

These rules focus on maintainability, readability, testability, and comprehensibility of your code. If you already write code that is maintainable, readable, testable, and comprehensible, then these rules will help you write code that is more maintainable, more readable, more testable, and more comprehensible.

In the following, I will review each of these 9 rules listed below:

- Only One Level Of Indentation Per Method

- Don’t Use The ELSE Keyword

- Wrap All Primitives And Strings

- First Class Collections

- One Dot Per Line

- Don’t Abbreviate

- Keep All Entities Small

- No Classes With More Than Two Instance Variables

- No Getters/Setters/Properties

1. Only One Level Of Indentation Per Method

Having too many levels of indentation in your code is often bad for readability, and maintainability. Most of the time, you can’t easily understand the code without compiling it in your head, especially if you have various conditions at different level, or a loop in another loop, as shown in this example:

class Board {

public String board() {

StringBuilder buf = new StringBuilder();

// 0

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

// 1

for (int j = 0; j < 10; j++) {

// 2

buf.append(data[i][j]);

}

buf.append("\n");

}

return buf.toString();

}

}

In order to follow this rule, you have to split your methods up. Martin Fowler, in his book Refactoring, introduces the Extract Method pattern, which is exactly what you have to do/use.

You won’t reduce the number of lines of code, but you will increase readability in a significant way:

class Board {

public String board() {

StringBuilder buf = new StringBuilder();

collectRows(buf);

return buf.toString();

}

private void collectRows(StringBuilder buf) {

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

collectRow(buf, i);

}

}

private void collectRow(StringBuilder buf, int row) {

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

buf.append(data[row][i]);

}

buf.append("\n");

}

}

2. Don’t Use The ELSE Keyword

The else keyword is well-known as the if/else construct is built into nearly

all programming languages. Do you remember the last time you saw a nested

conditional? Did you enjoy reading it? I don’t think so, and that is exactly why

it should be avoided. As it is so easy to add a new branch to the existing code

than refactoring it to a better solution, you often end up with a really bad

code.

public void login(String username, String password) {

if (userRepository.isValid(username, password)) {

redirect("homepage");

} else {

addFlash("error", "Bad credentials");

redirect("login");

}

}

An easy way to remove the else keyword is to rely on the early return

solution.

public void login(String username, String password) {

if (userRepository.isValid(username, password)) {

return redirect("homepage");

}

addFlash("error", "Bad credentials");

return redirect("login");

}

The condition can be either optimistic, meaning you have conditions for your error cases and the rest of your method follows the default scenario, or you can adopt a defensive approach (somehow related to Defensive Programming), meaning you put the default scenario into a condition, and if it is not satisfied, then you return an error status. This is better as it prevents potential issues you didn’t think about.

As an alternative, you can introduce a variable in order to make your return statement parametrizable. This is not always possible though.

public void login(String username, String password) {

String redirectRoute = "homepage";

if (!userRepository.isValid(username, password)) {

addFlash("error", "Bad credentials");

redirectRoute = "login";

}

redirect(redirectRoute);

}

Also, it is worth mentioning that Object Oriented Programming gives us powerful features, such as polymorphism. Last but not least, the Null Object, State and Strategy patterns may help you as well!

For instance, instead of using if/else to determine an action based on a

status (e.g. RUNNING, WAITING, etc.), prefer the State

pattern as it is used to

encapsulate varying behavior for the same routine based on an object’s state

object:

Source: http://sourcemaking.com/design_patterns/state

Source: http://sourcemaking.com/design_patterns/state

3. Wrap All Primitives And Strings

Following this rule is pretty easy, you simply have to encapsulate all the primitives within objects, in order to avoid the Primitive Obsession anti-pattern.

If the variable of your primitive type has a behavior, you MUST encapsulate

it. And this is especially true for Domain Driven Design. DDD describes

Value Objects like Money, or Hour for instance.

4. First Class Collections

Any class that contains a collection should contain no other member variables. If you have a set of elements and want to manipulate them, create a class that is dedicated for this set.

Each collection gets wrapped in its own class, so now behaviors related to the collection have a home (e.g. filter methods, applying a rule to each element).

5. One Dot Per Line

This dot is the one you use to call methods in Java, or C# for instance. It would be an arrow in PHP, but who uses PHP anyway? :D

Basically, the rule says that you should not chain method calls. However, it doesn’t apply to Fluent Interfaces and more generally to anything implementing the Method Chaining Pattern (e.g. a Query Builder).

For other classes, you should respect this rule. It is the direct use of the Law of Demeter, saying only talk to your immediate friends, and don’t talk to strangers.

Look at these classes:

class Location {

public Piece current;

}

class Piece {

public String representation;

}

class Board {

public String boardRepresentation() {

StringBuilder buf = new StringBuilder();

for (Location loc : squares()) {

buf.append(loc.current.representation.substring(0, 1));

}

return buf.toString();

}

}

It is ok-ish to have public attributes in Piece and Location. Actually,

having a public property or a private one with getter/setter is the same

thing (see Rule 9).

However, the boardRepresentation() method is awful, take a look at this line:

buf.append(loc.current.representation.substring(0, 1));

It accesses a Location, then its current Piece, then the Piece’s

representation on which it performs an action. This is far from One Dot Per

Line.

Fortunately, the Law of Demeter tells you to talk to your friends, so let’s do that:

class Location {

private Piece current;

public void addTo(StringBuilder buf) {

current.addTo(buf);

}

}

Making the instance of Piece private ensures that you won’t try to do

something bad. However, as you need to perform an action on this attribute, you

need a new method addTo(). It is not Location’s responsibility to determine

how the Piece will be added, so let’s ask it:

class Piece {

private String representation;

public String character() {

return representation.substring(0, 1);

}

public void addTo(StringBuilder buf) {

buf.append(character());

}

}

Then again, you should change the visibility of your attribute. As a reminder, the Open/Closed Principle says that software entities (classes, modules, functions, etc.) should be open for extension, but closed for modification.

Also, extracting the code to get the first character of the representation

in a new method looks like a good idea as it may be reused at some point.

Finally, here is the updated Board class:

class Board {

public String boardRepresentation() {

StringBuilder buf = new StringBuilder();

for (Location location : squares()) {

location.addTo(buf);

}

return buf.toString();

}

}

Much better, right?

6. Don’t Abbreviate

The right question is Why Do You Want To Abbreviate?

You may answer that it is because you write the same name over and over again? And I would answer that this method is reused multiple times, and that it looks like code duplication.

So you will say that the method name is too long anyway. And I would tell you that maybe your class has multiple responsibilities, which is bad as it violates the Single Responsibility Principle.

I often say that if you can’t find a decent name for a class or a method, something is probably wrong. It is a rule I use to follow while designing a software by naming things.

Don’t abbreviate, period.

7. Keep All Entities Small

No class over 50 lines and no package over 10 files. Well, it depends on you, but I think you could change the number of lines from 50 to 150.

The idea behind this rule is that long files are harder to read, harder to understand, and harder to maintain.

8. No Classes With More Than Two Instance Variables

I thought people would yell at me while introducing this rule, but it didn’t happen. This rule is probably the hardest one, but it promotes high cohesion, and better encapsulation.

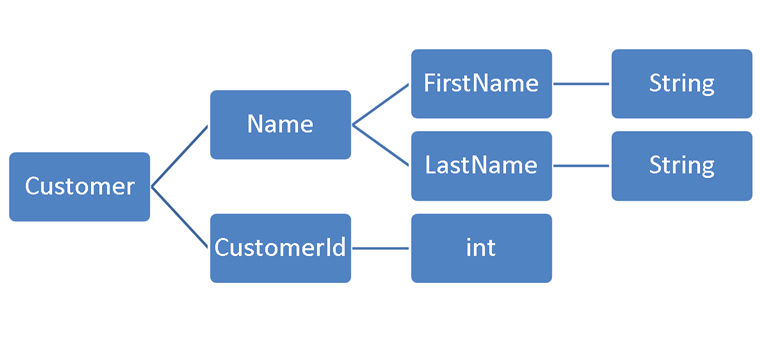

A picture is worth a thousand words, so here is the explanation of this rule in picture. Note that it relies on Rule 3: Wrap All Primitives And Strings.

The main question was Why two attributes? My answer was Why not? Not the best explanation but, in my opinion, the main idea is to distinguish two kinds of classes, those that maintain the state of a single instance variable, and those that coordinate two separate variables. Two is an arbitrary choice that forces you to decouple your classes a lot.

9. No Getters/Setters/Properties

My favorite rule. It could be rephrased as Tell, don’t ask.

It is okay to use accessors to get the state of an object, as long as you don’t use the result to make decisions outside the object. Any decisions based entirely upon the state of one object should be made inside the object itself.

That is why getters/setters are often considered evil. Then again, they violate the Open/Closed Principle.

Let’s take an example:

// Game

private int score;

public void setScore(int score) {

this.score = score;

}

public int getScore() {

return score;

}

// Usage

game.setScore(game.getScore() + ENEMY_DESTROYED_SCORE);

In the code above, the getScore() is used to make a decision, you choose how

to increase your score, instead of leaving this responsibility to the Game

instance.

A better solution would be to remove the getters/setters, and to provide methods

that make sense. Remember, you must tell the class to do something, and you

should not ask it. In the following, you tell the game to update your

score as you destroyed ENEMY_DESTROYED_SCORE enemies.

// Game

public void addScore(int delta) {

score += delta;

}

// Usage

game.addScore(ENEMY_DESTROYED_SCORE);

It is game’s responsibility to determine how to update the score.

In this case, you could keep the getScore() as you may want to display it

somewhere on the UI, but keep in mind that setters should not be

allowed.

Conclusion

If you don’t feel comfortable with these rules, it is ok, but trust me when I tell you that they can be used in real life. Try them in your spare time, by refactoring your Open Source projects for instance. I think it is just a matter of practice. Some rules are easy to follow, and may help you.

Slides

Links

- Object Calisthenics and Code Readability in PHP;

- Object Calisthenics Applied to PHP;

- Object Calisthenics by Jeff Bay.

TL;DR

9 steps to better software design today, by Jeff Bay:

- Only One Level Of Indentation Per Method

- Don’t Use The ELSE Keyword

- Wrap All Primitives And Strings

- First Class Collections

- One Dot Per Line

- Don’t Abbreviate

- Keep All Entities Small

- No Classes With More Than Two Instance Variables

- No Getters/Setters/Properties

ℹ️ Feel free to fork and edit this post if you find a typo, thank you so much! This post is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0) license.

Source:

Source: