SPI flash content analysis and firmware reconstruction

— Freiburg, GermanyI wrote a [Twitter thread about hardware hacking]1 some time ago.

The idea was to explain one way to obtain privileged access on a device. In

this case, the target was a cheap Chromecast-like device (more on that below)

and I “easily” got root access via UART.

This article explains how I reconstructed a modified firmware for this device.

Overview of the Chrome/Mira/Any-cast device

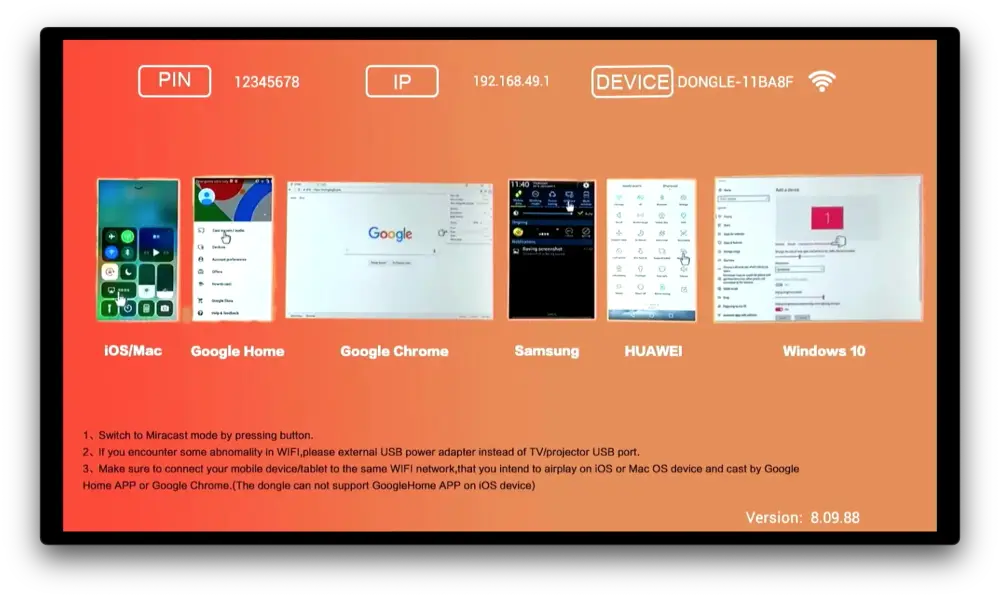

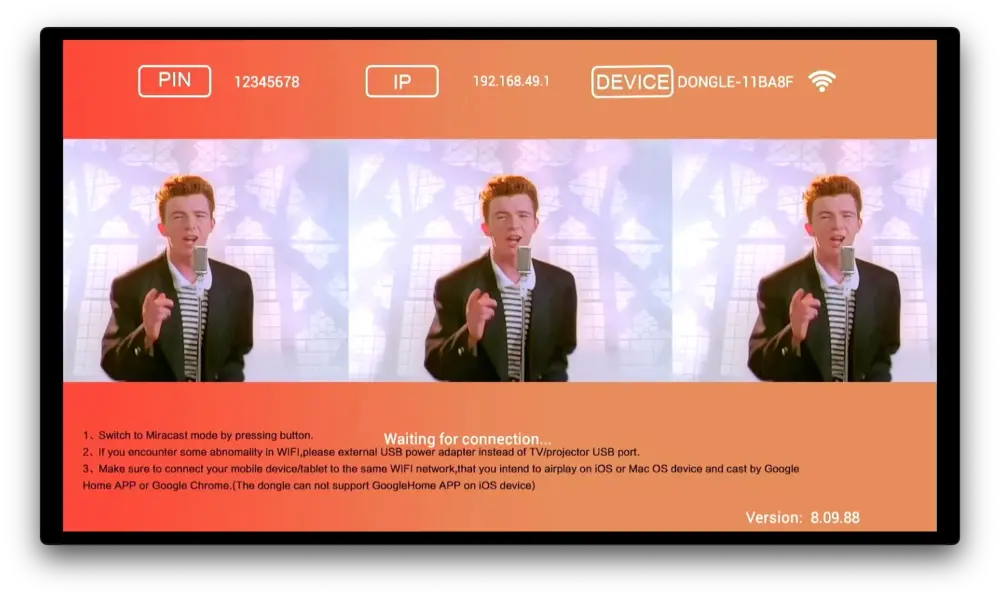

The target was a cheap Chromecast (or Miracast or Anycast) “clone” bought on Aliexpress (I am not sure because it was a “gift”). Such a device lets users cast audio and video on their TV as shown in Figure 1 (HDMI output). In addition to a HDMI connector, this device is bundled with an external WiFi adapter (USB).

Figure 1: A screenshot of the default HDMI output (taken with a capture card)

Figure 1: A screenshot of the default HDMI output (taken with a capture card)

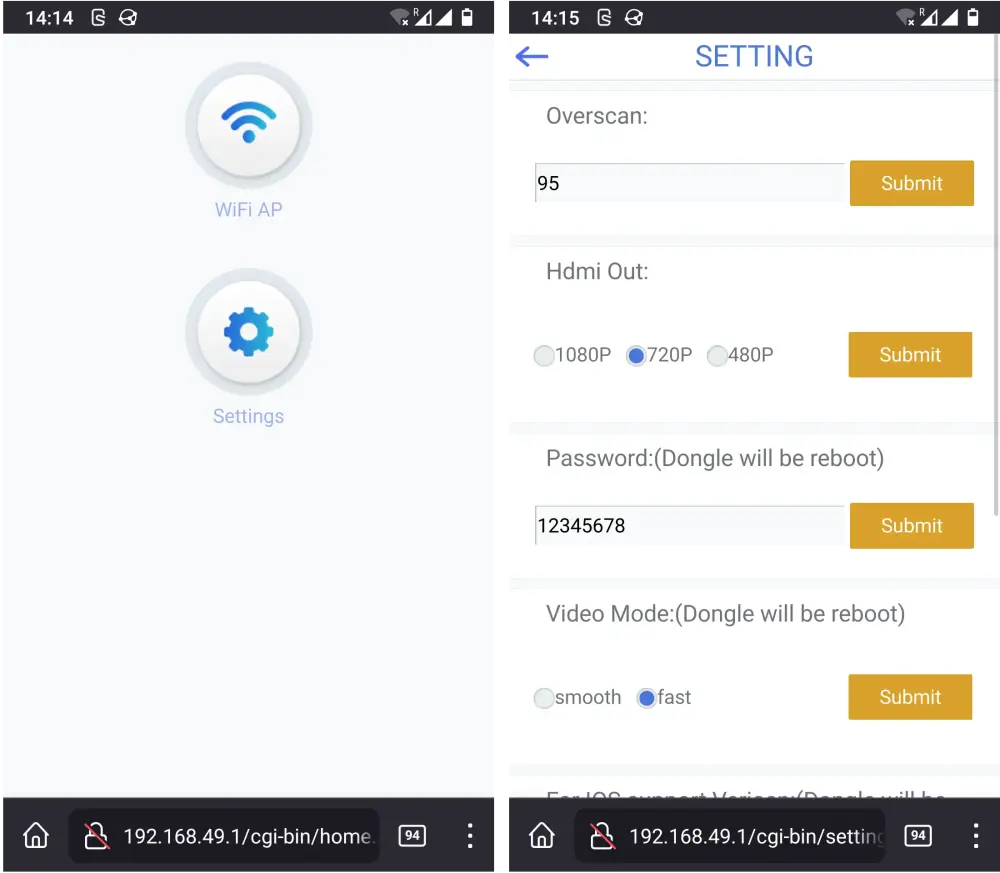

When the device is powered on for the first time, it creates a WiFi network,

e.g., DONGLE-11BA8F. Users should first connect to this network with their

smartphone or laptop, and configure the device using a web app as shown in

Figure 2. This step is necessary to allow the device to connect to the user’s

WiFi network.

Figure 2: Two screenshots of the web application

Figure 2: Two screenshots of the web application

Once the device has restarted and joined the user’s WiFi network, users can theoretically send audio or video to the device and have it played on TV. According to the manual, this device should work with the “Chromecast protocol” but it didn’t work that well for me.

I was able to cast audio and pictures but not video. Google Home wasn’t able to communicate with the device in a stable manner. I tried many different applications on both iOS and Android and I wasn’t able to achieve much. I tried to upgrade the device but the remote server was not found… These are the reasons why I decided to “hack” this device.

Besides having fun, my goal was to find ways to “fix” this device either by updating the software or re-purposing it. I knew it’d be complex but also that I’d learn a lot. At the time of writing, I didn’t achieve my goal yet but I made good progress.

I explained how I gained access to a Linux console in the Twitter thread so I am not going to repeat myself here. Instead, the rest of this blog post describes what happened next.

Diving into the content of the SPI flash

I was left with a full dump of the SPI flash (the storage component of this device) and many questions. I used binwalk to get an overview of the content of the SPI flash.

The dump contained a Linux kernel (the three first entries in the output below) and two file systems: Journalling Flash File System version 2 (JFFS2) and SquashFS.

$ binwalk flash.dump

DECIMAL HEXADECIMAL DESCRIPTION

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

264192 0x40800 Linux kernel ARM boot executable zImage (little-endian)

280492 0x447AC gzip compressed data, maximum compression, from Unix, last modified: 1970-01-01 00:00:00 (null date)

3292936 0x323F08 Flattened device tree, size: 49912 bytes, version: 17

4456448 0x440000 JFFS2 filesystem, little endian

5242880 0x500000 Squashfs filesystem, little endian, version 4.0, compression:xz, size: 10778932 bytes, 412 inodes, blocksize: 524288 bytes, created: 2020-12-02 03:03:01

I kindly asked binwalk to extract the SquashFS partition:

$ ls squashfs-root/

bin/ build.prop* etc/ fonts/ lib/ usr/ vendor/

In the Twitter thread, I mentioned that the device was running Android. This

SquashFS partition is very likely the system partition. Among other things, it

contains the content of the web application described in the previous section.

Each page is a CGI ELF binary:

$ file squashfs-root/bin/home.cgi

squashfs-root/bin/home.cgi: ELF 32-bit LSB shared object, ARM, EABI5 version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /system/bin/linker, stripped

After a few Google/GitHub searches, I had found extremely similar sources of these CGI files. None of these scripts seemed particularly interesting, though.

I also took a quick look at the JFFS2 partition, which appeared to be the data

partition (of an Android-based system) but I didn’t find anything useful either.

Last, I used fdtdump to explore the device tree, i.e. the “hardware configuration” of this device for the Linux kernel (Android uses the Linux kernel). This gives an idea of which hardware may be present and how it should be used by the kernel, and it could be useful information later.

After that, I looked at the structure of the SPI flash.

MTD partitions

Based on the kernel logs I had captured when I was using the Linux console over serial, I knew the content was divided into 5 different partitions: loader, kernel, data, system and misc.

[ 0.379500] Creating 5 MTD partitions on "rk29xxnand":

[ 0.379538] 0x000000000000-0x000000040000 : "loader"

[ 0.380859] 0x000000040000-0x000000440000 : "kernel"

[ 0.382175] 0x000000440000-0x000000500000 : "data"

[ 0.383466] 0x000000500000-0x000000ffd000 : "system"

[ 0.384697] 0x000000ffd000-0x000000ffe000 : "misc"

Out of 5 MTD partitions, 3 have been seen previously: kernel, data and

system. Note that the kernel partition starts at 0x40000 but binwalk

found the zImage at 0x40800. We’ll get back to that in a moment. For data

and system, the offsets in the binwalk output match the base addresses in

the logs above.

This time, I used dd to split the original dump into different binary files

based on the address ranges printed in the kernel logs above. I then looked at

each file individually, and made the following observations:

kernel.binis not recognized byfile, weird.- although

data.binandsystem.binare correctly detected as file systems byfile, the.binfiles extracted withddseem different than the files extracted withbinwalk. Maybe becausebinwalktried to find magic numbers and metadata (like the size of the content it has to extract)? I am not sure. misc.binis an “empty” binary file.

$ file *.bin

loader.bin: data

kernel.bin: data

data.bin : Linux jffs2 filesystem data little endian

system.bin: Squashfs filesystem, little endian, version 4.0, xz compressed, 10778932 bytes, 412 inodes, blocksize : 524288 bytes, created : Wed Dec 2 03:03:01 2020

misc.bin : ISO-8859 text, with very long lines, with no line terminators

Given I had already analyzed the “data partitions” (data and system), I

decided to study the loader and kernel partitions next.

The loader partition

I ran strings on the loader.bin file, which returned a few strings that I

already read before. Indeed, this partition contains the code that loads the

Linux kernel and some of the strings found in the binary appeared in the boot

logs collected over serial:

DDR Version 1.08 20170609

In

DDR2

396MHz

BW=16 Col=10 Bk=8 Row=13 CS=1 Size=128MB

OUT

0 BUILD: Apr 13 2018 09:17:13, version: 1.24

sfc nor id: c2 20 18 10 3c

g_spi_flash_info id 0x00c22018.

AddrMode: 0

ReadLines: 0

ProgLines: 0

ReadCmd: 3

ProgCmd: 2

blkEraseCmd: d8

secEraseCmd: 20

boot_media = 0x10

flash vendor_storage_init

OK! 21154

loader flag: 0x0

start_linux=====258615

multi-entries loader - fw_status: 0x1, kernel_addr 200, 259 ms

enter LoadKernel @263 ms

hdr.loader_load_size= 2efa00

hdr.loader_load_addr= 62000000

load kernel data done @1043 ms

run kernel@0x62000000 =====1043 ms

loader update successfully =====1046 ms

<hit enter to activate fiq debugger>

[ 0.000000] Booting Linux on physical CPU 0xf00

...

It looks like the bootloader is named “DDR” and the version is 1.08. I found

binaries for other versions of this bootloader on the web but not for

the version I had (huh?), and no source code.

I also ran hexdump on loader.bin and was faced with the following output:

00000000 52 4b 46 50 e4 07 0c 02 0b 03 0e 00 19 00 05 10 |RKFP............|

00000010 00 02 00 00 01 00 00 00 f0 7f 00 00 80 00 00 00 |................|

00000020 06 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

00000030 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

*

000001f0 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 98 45 32 7b a8 8a fb fa |.........E2{....|

00000200 76 65 6e 64 6f 72 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |vendor..........|

00000210 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

00000220 01 00 00 00 08 00 00 00 38 00 00 00 00 70 00 00 |........8....p..|

00000230 00 00 00 00 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

...

I tried to find more information about the RKFP magic number. There isn’t a

lot of information about it. This seems to be a proprietary image format but its

structure is partially known and open source. I found the definitions of the

different structures in rkflash_blk.h (Linux kernel) and

this page helped a lot by providing additional context!

The kernel partition

I read the kernel.bin file with hexdump. The first few bytes are shown

below:

$ hexdump -C part-kernel.bin

00000000 4b 45 52 4e 45 4c 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |KERNEL..........|

00000010 00 00 00 62 00 fa 2e 00 cc ec ad 80 20 00 00 00 |...b........ ...|

00000020 7a 46 9d 1b 84 4d be a7 59 81 3a 48 d2 19 67 a4 |zF...M..Y.:H..g.|

00000030 79 9c d3 78 d9 3f d6 5a c7 34 03 ec 1b 09 84 b9 |y..x.?.Z.4......|

00000040 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

...

This looks like some kind of partition header. That’s odd because (1) the other

partitions don’t appear to have any header like that, and (2) I only found

RockChip tools that deal with images with KRNL as magic number, not KERNEL.

Ugh.

In the hexdump output above, I noticed two values on the second line that

looked familiar. Indeed, in the bootloader logs, there were these two lines:

hdr.loader_load_size= 2efa00

hdr.loader_load_addr= 62000000

The load address is therefore at offset 0x10 in this “kernel header”, and the

(kernel?) size is at offset 0x15. Then we have another 4 bytes, which seems to

be the CRC for this header. The next 4 bytes hold a value of 0x20 and that

looks like the length of the following bytes (from 0x20 to 0x40). Some

checksum, maybe? This could be the length of a SHA-256 hash.

After this header, there is some padding until offset 0x800 where we find some

ARM instructions (00 00 A0 E1). This explains why binwalk found the kernel

at 0x40800 before.

At this point, I had enough information about the content of the SPI flash. As stated at the top of this blog post, my goal was to fix this device. Writing a parser for these RKFP images would be a good first step to be able to update the firmware eventually.

Parsing RKFP images

I developed a tool in C to print information about RKFP images. I also found two other similar (SPI flash) dumps in the wild, allowing me to have more examples while developing my tool. In particular, it turned out that the image I had dumped myself had a CRC mismatch 😅

$ ./build/cli info flash.dump

Input file:

name: flash.dump

size: 16777216 bytes

Header:

firmware tag : RKFP

firmware version : 16.05.25

release date : 2020-12-02 at 11:03:14

size : 512 bytes

partition_offset : 1 sectors

backup_partition_offset: 32752 sectors

partition_size : 128 bytes

partition_count : 6

fw_size : 0 bytes

partition_crc : 0x7B324598

header_crc : 0xFAFB8AA8

CRC:

WARNING! header CRC mismatch (got 0x74B94941)

partition CRC: OK

Partition #00 - 0x00001000-0x00008000

name : vendor

type : 0x01

offset : 4096 bytes (0x1000)

size : 28672 bytes (0x7000)

data size: 28672 bytes (0x7000)

property : 0x00

Partition #01 - 0x00008000-0x00038000

name : IDBlock

type : 0x02

offset : 32768 bytes (0x8000)

size : 196608 bytes (0x30000)

data size: 86016 bytes (0x15000)

property : 0x00

Partition #02 - 0x00040000-0x00440000

name : kernel

type : 0x04

offset : 262144 bytes (0x40000)

size : 4194304 bytes (0x400000)

data size: 3080708 bytes (0x2F0204)

property : 0x00

Partition #03 - 0x00440000-0x00500000

name : data

type : 0x08

offset : 4456448 bytes (0x440000)

size : 786432 bytes (0xC0000)

data size: 786432 bytes (0xC0000)

property : 0x00

Partition #04 - 0x00500000-0x00FFD000

name : system

type : 0x0C

offset : 5242880 bytes (0x500000)

size : 11522048 bytes (0xAFD000)

data size: 10780672 bytes (0xA48000)

property : 0x00

Partition #05 - 0x00FFD000-0x00FFE000

name : misc

type : 0x0F

offset : 16764928 bytes (0xFFD000)

size : 4096 bytes (0x1000)

data size: 0 bytes (0x0)

property : 0x00

Most partitions were not new because they were listed as “MTD partitions” and I

had already analyzed some of them. The tool found 6 RKFP partitions, though.

Instead of having a loader partition, we had two partitions: vendor and

IDBlock. “ID Block” is apparently a header for Rockchip BootRom.

Next, I wrote a new command (extract_rkfp) to extract the actual data located

in each RKFP partition. It is worth mentioning that I later found the

rkflashtool project, which offers a tool to unpack RKFP images too (among

other things). Both this tool and mine were producing identical partition

files.

At this point, I was able to read information from a RKFP image, verify the different CRCs and extract the data contained in each partition. I had two options: (1) stop there and forget about this project, or (2) find out how to make a RKFP image 😬

Reconstructing RKFP images

I tried to reconstruct the RKFP images I had (the one I dumped and two I found

online). My idea was to invert the “read” process by appending the different

RKFP partitions extracted with make_rkfp after having written a “RKFP header”.

Obviously, this didn’t work… I used VBinDiff (a lot) to compare the

original image and the one I had reconstructed with my tool. The header appeared

to be correct but there were differences in the IDBlock partition and in some

other locations.

I realized that the IDBlock partition was special: although it had a data size

of N, its actual size was almost three times bigger and after having inspected

its content, I had the impression that there was more data than what the

partition metadata was saying. Some more searches about this mysterious

setting.ini file mentioned here made me conclude that there

were probably two loaders. Given that this partition likely contained

proprietary code that I needed anyway but didn’t necessarily need to change, I

adjusted my tool. I special-case’d the IDBlock partition so that the entire

partition was (1) extracted with extract_rkfp, and (2) written with

make_rkfp.

I could then generate a RKFP image that looked almost like the original one. The images I found online had extra “backup metadata”, which I didn’t have in the image coming from my device. I wrote code for that, too.

I was kinda confident with my tool but I hadn’t tried the new images on the device yet so its effectiveness was purely theoretical.

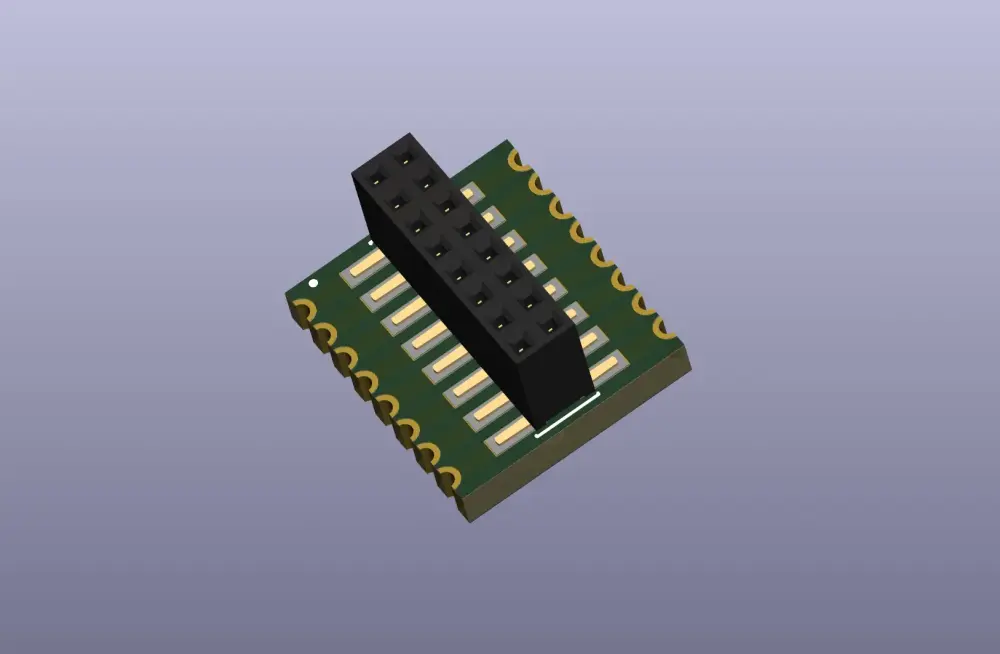

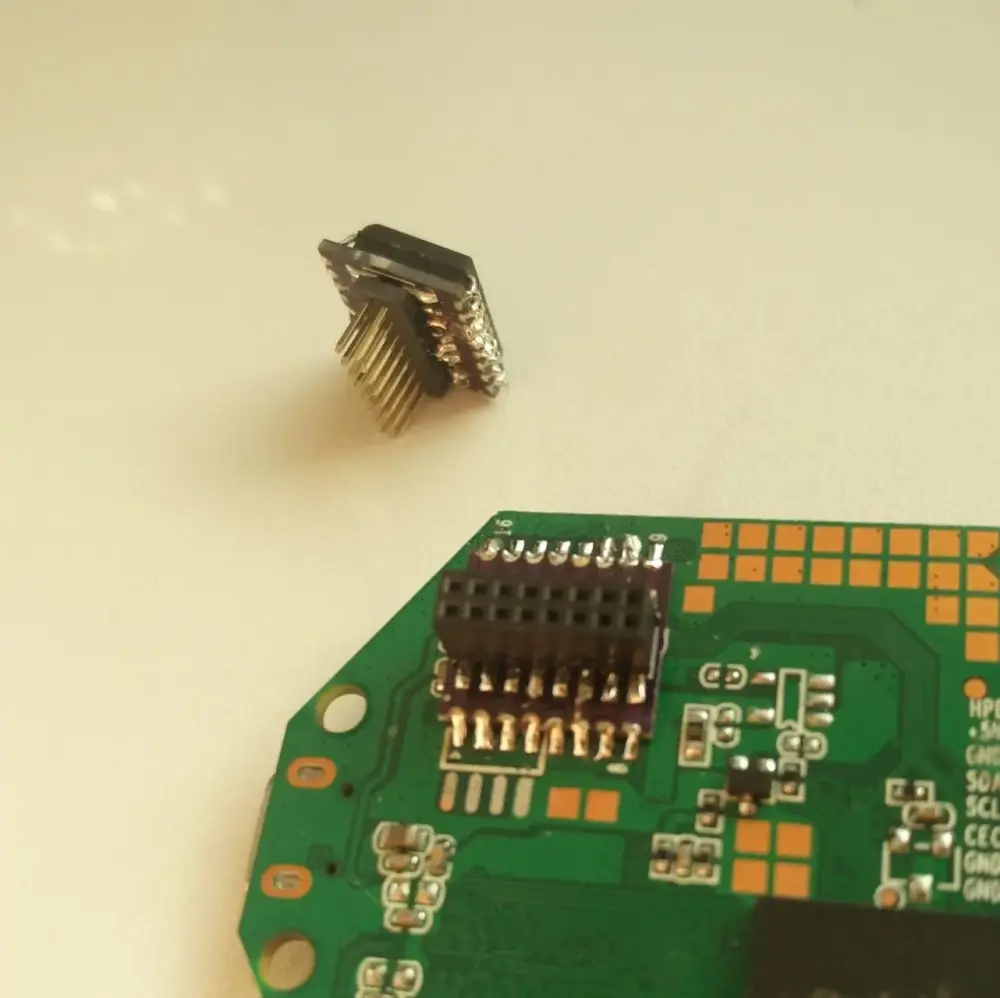

A breakout board for SOIC-16

In order to verify that my tool was producing correct firmware, I needed a way to write to the SPI flash chip and then boot the device. Near the end of the Twitter thread, the flash had been desoldered. Soldering and desoldering the flash every time was not an option, and I couldn’t properly use flashrom when the flash was soldered on the device.

I decided to design a small PCB to get access to the flash pins using a 1.27mm 16-pin socket, which would be soldered on the device (see Figure 3). The same board could also be reused with a plug on one side and the flash chip on the other side (see Figure 4).

Figure 3: The 3D view of the breakout board for SOIC-16

Figure 3: The 3D view of the breakout board for SOIC-16

It was the first time I designed a PCB with castellated holes. OSH Park did an amazing work on such small boards (about the size of 1 cent coins) 😍

second breakout board

holds the SPI flash + a plug on the other side

With these breakout boards assembled (see Figure 5), I could easily write to the flash and test my changes on real hardware. Before that, I made sure that the device could still boot with the original firmware (still present on the flash).

Figure 5: The SPI flash mounted on the device (blue circle)

Figure 5: The SPI flash mounted on the device (blue circle)

I then used flashrom to put the reconstructed (unmodified) firmware on the SPI flash and I powered on the device. Success! The device booted and everything seemed to work as before.

My next experiment was about producing and booting a modified firmware.

Modifying the system partition

I opted to change the system partition. The first step was to know which options to use to rebuild the SquashFS partition:

$ unsquashfs -s part-system.bin

Found a valid SQUASHFS 4:0 superblock on 500000.squashfs.

Creation or last append time Wed Dec 2 04:03:01 2020

Filesystem size 10778932 bytes (10526.30 Kbytes / 10.28 Mbytes)

Compression xz

Dictionary size 524288

Filters selected: arm

Block size 524288

...

I changed a file in the extracted content and then rebuilt the partition:

$ mksquashfs squashfs-root new-system-partition.bin -comp xz -Xbcj arm -b 524288 -all-root

I then reused the make_rkfp command to create a new RKFP image and loaded it

on the SPI flash, then put the flash back on the device and powered it on. 3..

2.. 1.. Success! 😎

Figure 6: HDMI output with the modified firmware

Figure 6: HDMI output with the modified firmware

Work in progress

Only the system partition has been altered in the previous section but the

data partition could have been equally modified. I had no interest in changing

the loader partition and the misc one was empty. This leaves us with the

kernel partition.

I added a extract_kernel command to my tool to extract the data from the

kernel partition. This was a requirement to understand how to make such a

kernel partition in the future, the main motivation being to eventually update

the version of the Linux kernel.

The extracted data appears to be a zImage with DTB files appended to it. I am

not too sure how that has been generated yet, maybe just cat zImage *.dtb > kernel?

A initial ramdisk seems to be part of that same zImage too, and it

contains different init.*.rc files.

The next steps will be to build a new Linux kernel that looks like the extracted one, and see if that works.

Conclusion

After having gained root access on this device, I have been able to modify the

original firmware. Out of 5 MTD partitions, all but two have been fully analyzed

(loader and kernel). I designed a breakout board to easily verify firmware

produced with a tool I created specifically for this project. This was also a

good excuse to learn about modern CMake 😉

As mentioned before in this article, I was not too interested in the loader

partition, hence my focus on the kernel partition near the end. In the future,

I want to build a new kernel image and load it on the device. There are two

known issues so far: (1) building the right (Android) kernel for the device, and

(2) creating a kernel partition for the RKFP image. We’ll see how it goes…

Last but not least, both the tool and the KiCad files have been published on GitHub. Enjoy!

-

This used to be a link to a Twitter thread from me. I documented how I gained (root) access on a cheap device, which involved hardware and software skills. ↩

ℹ️ Feel free to fork and edit this post if you find a typo, thank you so much! This post is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0) license.